Difference between revisions of "Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience"

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| − | {{: | + | {{:Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience/Introduction}} |

| − | {{: | + | {{:Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience/Zoom Metaphor}} |

| − | {{: | + | {{:Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience/The Frame}} |

| − | {{: | + | {{:Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience/Bulletin Boards}} |

| − | {{: | + | {{:Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience/View Source}} |

| − | {{: | + | {{:Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience/The Journal}} |

| − | {{: | + | {{:Human Interface Guidelines/The Laptop Experience/Global Search}} |

Latest revision as of 09:03, 7 July 2009

The Laptop Experience

Introduction

Most developers are familiar with the desktop metaphor that dominates the modern-day computer experience. This metaphor has evolved over the past 30 years, giving rise to distinct classes of interface elements that we expect to find in every OS: desktop, icons, files, folders, windows, etc. While this metaphor makes sense at the office—and perhaps even at home—it does not translate well into a collaborative environment such as the one that the OLPC laptops will embody. Therefore, we have adopted a new set of metaphors that emphasize community. While there are some correlations between the Sugar UI and those of traditional desktops, there are also clear distinctions. It is these distinctions that are the subject of the remainder of this section. We highlight the reasoning behind our shift in perspective and detail functionality with respect to the overall laptop experience.

| API Reference |

|---|

| Sugar |

| Package sugar.shell |

- Desktop : Neighborhood

- Menubar : The Frame

- Hierarchical Filesystem : Journal

- Applications : Activities

- Files : Objects

Zoom Metaphor

The mesh network is a permanent fixture of the laptop environment and is represented explicitly in the interface. A zoom is used to relate four discrete views, each of which caters to a particular set of goals: Home, Groups, Neighborhood, and Activity. Using keyboard shortcuts or controls in the Frame, children may zoom in and out on the mesh community.

| API Reference |

|---|

| Package sugar.shell.view.home |

Home

- See Activity Management for new design images.

Of all the zoom levels, the Home view relates most closely to the traditional desktop. As the first screen presented to the child at startup, it serves as a starting point for the exploration of both the mesh network and also of personal activities and objects. From this view, the child may either back up first to their Groups — such as their Friends or their Class — and beyond that to a view of the entire mesh Neighborhood, or, instead, zoom in to focus on a particular Activity.

The Home view interface is minimalistic. In the center of the screen, the XO icon—rendered in the child's user-specified colors—represents the child to whom the laptop belongs. The activity ring surrounds the character, indicating all of the currently open activities. Furthermore, the section of the ring that a given activity occupies directly represents the amount of memory that the particular activity requires to run, providing immediate visual feedback about memory constraints and exposing a means for resource management that doesn't require knowledge of the underlying architecture. Most activity management happens here: starting new private activities, ending current activities, and switching between activities.

| API Reference |

|---|

| Package sugar.shell.view.home.activitiesdonut |

When used in conjunction with the Bulletin Board, the Home view becomes the most direct correlate to a typical PC desktop as a place for keeping things handy: tomorrow's homework, a drawing one is working on, a favorite song, a reminder to oneself to do one's chores, etc.

Groups

The Groups view takes a small step back from the child's Home space, opening up to include their circle of friends, their classmates, and any other groups to which a child belongs. The Friends group essentially represents a spatially viewable and editable buddy list. From here the child can add or remove friends and move individuals around, perhaps arranging them logically. The Class group is defined dynamically, and includes all others in the same class, and their teachers as well. This group provides the perfect space for working and sharing with classmates, posting projects for class critique, or for picking up the homework assignment the teacher posted to the class Bulletin Board.

In addition to several special classes of groups, children may also generate groups on their own. This might provide a way for a close group of friends to keep up with each other's activities, or for a group of aspiring photographers to share photos. In a classroom setting, this provides a way for the children to create temporary groups for working on classroom exercises, or long term groups for extended projects. To create a group, a child can search for or select any number of individuals on the mesh. Each of these individuals will receive an invitation to join the group, and upon accepting the invitation will have its name added to their list of Groups, where they can see and chat with members, and post to the group Bulletin Board. Although one person initially creates a group, groups are not managed. Instead, people may choose to leave a group on their own, and anyone in the group may invite other members into it. When this happens, all current group members receive introduction notification, making them aware of the new member. This open model simplifies the interaction and encourages the learning of natural social dynamics instead of attempting to enforce them via rules and restrictions.

| API Reference |

|---|

| Package sugar.shell.view.home.FriendsBox |

Groups have several advantages. First, it allows the children to view their friends, classmates, and other groups, and allows them to freely chat with them as well. Additionally, each group will have its own private Bulletin Board where members can post notes and share Objects. Finally, all of the members of the selected group — a child's friends, for instance —receive invitations whenever the child starts an activity from the Groups view, making collaboration implicit. Moreover, this view allows the child to see what activities their class, friends, and other groups are presently engaged in, providing the opportunity to join any non-private activities. Already, you can see how this view changes the usual method of application launch, allowing one to start new networked activities or join existing ones directly.

Neighborhood

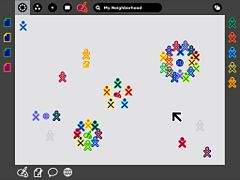

Zooming out one more step we reach the Neighborhood view. Here children can see everyone on their local mesh. At this level we intend to support a variety of views, each with a different focus: the individuals; the activities in which they are presently engaged; etc. In the figure, individuals are shown clustered around their currently active activities, providing a direct visual representation of the popularity of an activity, since group size is immediately perceptible.

While the Neighborhood view doesn't currently provide any true spatial or geographical data, it does provide an at-a-glance social geography of the mesh and its participants. Similar to the Groups view, launching an activity here implicitly opens that activity up for anyone in the Neighborhood to join. While no one receives an explicit invitation in this case, the newly started activity will appear in the view, with its participants clustered about it, so that anyone who wishes to may join. Of course, this also means that the Neighborhood provides an excellent space for exploration. Here, one can both search for, locate and join activities of interest using a powerful and adaptable search technology, and also interact with and make friends with other children in their neighborhood they haven't yet met.

| API Reference |

|---|

| Package sugar.shell.view.home.MeshBox |

Activity

Zooming in from the Home view, a child finds the Activity view. This view contains the activities where all of the actual creation, exploration, and collaboration takes place. This is where you, the developer, come into play, providing new and engaging tools, extending the functionality and encouraging new types of creative exploration.

Though multitasking has become somewhat of a standard in today's desktop computing world, we've chosen to break away from this model, instead adopting a fullscreen activity view that focuses the children's energies on one specific task at a time. Although one may have several activities open in the activity ring at any given moment, only one can be denoted as the active activity (similar to focus in a window system). Several factors contributed to this decision: first, although the laptops have an extremely high-resolution display—200dpi—the actual viewing area remains quite small—a modest 7.5-inch diagonal—leaving little room for multiple activities on the screen; second, as noted, it naturally focuses efforts on a specific task. The Frame detailed below serves as the interstitial tissue between activities. As a visual extention of the Journal, it enables objects to move between activities.

For extensive detail on the various aspects of the activity interface and their design guidelines, see the Activities section.

The Frame

- See Frame for new design images.

Always Available on the Periphery

Glancing at the previous screen shots, you might have noted the absence of a menu bar or other form of persistent interface element. Such a persistent element reduces the screen space available for activities; since screen is at a premium, we have opted to use a frame—always on the periphery and just out of sight—to contain all of the peripheral information that a child might need, across all views. Since the Frame persists at all zoom levels, it provides a consistent place for those interface elements which apply to all views, including search, incoming invitations and notifications, a clipboard, and buddies you are currently interacting with.

When activated, the Frame slides in atop the currently visible view, providing access to needed functionality, yet quickly retracting from view once the task for which the child invoked it ends. Although these transitions happen quickly, a forgiveness parameter prevents unintentional Frame retraction in hopes of making interaction with this interface element completely natural.

Frame Components & Organization

At a high level, one can consider the frame in two parts: The left, top, and right sides of the frame represent nouns: things, places, and persons. The bottom of the frame represents those elements that require action: activities, invitations, and notifications. More specifically, each edge of the frame is dedicated to one of people, places, objects, or actions.

People

| API Reference |

|---|

| Package sugar.shell.view.frame |

| Module: ...frame.FriendsBox |

| Module: sugar.shell.model.BuddyModel |

As previously mentioned, the presence of others on the mesh defines much of the laptop experience. In order to surface this at all times in the interface, the right-hand edge of the Frame provides an easily accessible list of all the individuals a child is collaborating with in the currently active activity, represented by their colored XOs. This has a number of benefits. First, it provides a quick reference of the people the child is working with, which updates as new people join and others leave. As new people arrive, they appear in the upper right corner, and as they leave they simply vacate their current location. Additionally, the secondary rollovers for these XO objects reveal biographical information about them: name, age, class, interests, and even a small photo. This makes the frame a great resource for meeting new friends, for what better place to meet them than in the activity shared with them?

Places

| API Reference |

|---|

| Module: ...frame.ZoomBox |

Of the various frame components, the Places category is the most abstract. However it also emphasizes the metaphors that the zoom levels build upon. In the upper left-hand corner reside the zoom buttons, which can instantly transition the user among the Activity, Home, Groups, and Neighborhood views. For clarity, the upper left-hand function buttons on the keyboard have identical icons and functionality.

On the other side of the Places edge resides the Bulletin-Board button. Again, this button has an analogous key on right-hand side of the keyboard's function keys. Discussed later, this button acts as a toggle for an auxiliary layer which can provide contextual chat and a place to share objects. This button functions within the Places bar because it acts as a modifier to any view. In a sense, it adds an additional layer of context to any other "place" on the laptop.

Finally, though not less importantly, this section of the Frame contains the global search field.

Objects

| API Reference |

|---|

| Module: ...frame.clipboardpanelwindow |

The clipboard has become a staple in any modern operating system. Nonetheless, its implementations have changed little, if at all, in decades. The clipboard has one "page", to which you can copy to, cut to, and paste from, and in most cases this hypothetical page remains invisible: to see what's on it, you've got to paste its contents. While this isn't strictly true (On Mac OSX, for instance, an item at the bottom of the 'Edit' menu allows you to 'View Clipboard Contents'), most users are oblivious about viewing its contents, as one must explicitly seek it out. This basic model, while simple, often falls short of many use cases. Thus, OLPC has extended the traditional clipboard, empowering the user with added functionality without increasing complexity.

On the laptops, the clipboard takes the form of the left-hand edge of the frame. This region serves as temporary storage for objects - a paper, an image, a sentence, a URL - facilitating their transfer among activities and, perhaps more importantly, among the various zoom levels. Any type of object that can be stored in the Journal can likewise be transported via the clipboard. A child may place an object on the clipboard in a couple of convenient ways. First, keyboard shortcuts will provide an interface for simple copy and paste functions in the way already familiar to us. Additionally, since objects support direct manipulation, the child may simply drag a photo, file, or selection onto the frame in order to copy it, and may then drag it out to paste it in another location, such as within another activity, on a friend, or to a Bulletin Board. As items are placed on the clipboard, they are arranged temporally in a push-down stack, the most recent clipping appearing in the upper-lefthand corner of the frame.

With the presence of a clipboard which contains multiple items, it becomes necessary to add a means for selecting an active clipping as the source for any paste command. Since the usual copy/paste keystrokes will quickly become familiar to all, any invocation of the copy shortcut will automatically place the resulting clipping at the top of the stack, selecting it as the source, so that a subsequent paste command behaves as expected. When not using these traditional shortcuts, a single click on any object in the clipboard will select it, visibly indicating it as the new source. Additional copy commands (or drags) will continue to add elements to the clipboard stack. Once the clipboard reaches a predefined limit, the elements at the bottom of the stack will begin to drop off making room for the new ones. Elements may also be removed explicitly by the user via their contextual rollover, and a modified paste shortcut for advanced users will serve to both paste an item and pop it from the stack at the same time.

The resulting clipboard will behave identically to those on current operating systems, while at the same time providing drag and drop support, clipboard history, and previews, as well as advanced functionality for advanced users.

Actions

| API Reference |

|---|

| Module: ...frame.ActivitiesBox |

The bottom edge of the frame functions primarily as an activity launcher, but it also accumulates both incoming invitations and notifications. As a starting point for instantiating activities, this part of the frame is fairly straightforward. Whenever an activity receives a click, a colored instance of that activity appears within the activity ring in the child's own colors, and invitations are automatically sent as appropriate. On the other hand, anytime the child receives an invitation it appears as a colored activity icon (in the color of the inviting XO, of course), clearly distinct from the uncolored outlines of the activities which reside on the child's own machine. Since an invitation to join an activity has no functional differences from starting, the invitations appropriately indicate this by their similar form. The rollover state for these invitations allows the child to accept or decline the invitation, optionally providing a reason for declining.

Notifications, the third aspect of the Actions edge of the frame, function slightly differently. While they don't represent an activity that the child can join, they do come as messages from activities or from the system, conveying important information about the state of the activity or system status such as battery strength or wireless signal. Though slightly different from activities and invitations, these notifications still require some action on the child's part, and are an appropriate addition to the frame which provides a convenient way to access them from within any view. Just as in the other edges of the frame, invitations and notifications organize by time, the most recent always in the lower left-hand corner, so that the child may handle them in a timely manner.

Activation Methods

The Frame has multiple activation methods.

Hot Corners

Hot corners serve as the Frame's primary invocation method. As Fitts' Law implies, the corners are the easiest part of the screen to hit with a cursor. Moving the cursor to any corner of the screen will instantly invoke the frame. From a corner, one can readily scroll along an edge in search of a desired element. Since newly added people, objects, and invitations insert from the corners, the latest invitation, clipping, or participant is always close at hand.

Function Key

In addition to trackpad-based activation, the information within the Frame lies just one keystroke away. A dedicated key has two modes of functionality: (1) momentary presses act as a toggle, turning the Frame on and off with each press; and (2) holding the key down, the Frame will appear on screen until release of the key. This latter method provides a quick way to glance at incoming invitations or other system status elements for a brief moment and then return full focus to the activity view itself.

Notification Overrides

Though rare, some urgent notifications such as low battery levels may override the Frame, automatically bringing it into view without user interaction. These overrides come from the system only; applications do not have privileges for override, although they may alert the user via standard notifications.

Bulletin Boards

Since the laptops have implicit connectivity via the mesh network, an additional layer of the UI has been designed to take advantage of it: Bulletin Boards. Taken literally, the Bulletin Boards provide a space for posting things.

Context is key to the usefulness of Bulletin Boards on the laptops. A button in the Places edge of the Frame toggles the Bulletin Board layer on and off, and although only one button exists for this purpose, each view among the various zoom levels has its own Bulletin Board. The scope of individuals who have access to a given Bulletin Board matches the scope of individuals that the view currently represents. For example, any items posted to the Home view Bulletin Board may only be seen by the child that posted them, effectively providing a traditional desktop environment. Likewise, anyone within the child's list of Friends may view things the child has posted to the Friends view Bulletin Board, and all of a child's classmates and her teacher can view her posts to the Class Bulletin Board; the Mesh view Bulletin Board provides an environment for sharing with the entire laptop community. Furthermore, each activity has its own Bulletin Board, providing a space for sharing files and ideas surrounding the activity itself that don't have a place within it.

Spatially Contextual Chatting Interface

As a transparent layer above any view, the Bulletin Board provides a spatially contextual chatting interface. This means that, unlike traditional forum-style threads that organize temporally, chat bubbles may be freely positioned on screen. Discussions formulate around specific areas of the activity beneath. Annotation-style comments open the door to a wide variety of conversational interactions. In a drawing of the ocean, for instance, one conversation could be happening below the water's surface, while another group of children discuss what kind of birds fly through the sky. In another situation, one child could remotely assist another in learning how to use a new activity, pointing out specific interface elements with detailed descriptions of their functionality. In a literary application, child or teacher could proofread another child's story, correcting spelling mistakes, pointing out grammatical errors, and sharing thoughts about specific sections of the story without directly editing the work on the activity layer beneath.

An Environment for Sharing

In addition to contextual chats, Bulletin Boards provide a space for sharing. Any object may be posted to a Bulletin Board for others to look at and enjoy and to pass on to others, promoting viral sharing. The sharing environment is an integral element of all views.

In the Home view, for instance, only the child to whom the laptop belongs has access to the contents of the Bulletin Board. Here, the Bulletin Board provides a convenient area for the temporary storage of objects and activities, as well as those things kept around for quick access: tomorrow's homework assignment, the pictures taken last week, the book the child is reading, a favorite game. In this way, the traditional desktop that the zoom levels replaced finds its way back through the Home view Bulletin Board. The functionality described here mimics the traditional desktop to some extent. Note that the contextual chat bubbles are also available in the Home view, providing a mechanism for writing "notes-to-self". The Bulletin Board metaphor emphasizes a temporary and ever changing space for placing objects, distinctly separate from the space in which they are stored. This may prevent the common overuse of the desktop as the primary place to store everything, which limits its usefulness as a quick way to find the files that matter most at any given point in time.

From the Friends and Mesh view, the Bulletin Board serves as a place to share interesting things a child has found or created with friends, and the entire mesh respectively. The important thing to remember with regard to sharing, of course, is that "Share this JPEG (or GIF or SVG or any other picture format) file with Bob and Sue" translates to "Share this photo (or picture) with Bob and Sue." The sharing metaphor functions much more naturally than the file transfer systems we're used to, since file transfer really just represents a technical implementation of the more abstract idea of sharing in the first place. Of course, children can also view the things that others have posted as well. Moreover, as a community space, group sharing occurs naturally.

Finally, the shared space the Bulletin Boards provide take on a slightly different, yet quite powerful meaning at the Activity level. Again, contextual to the current view, each activity has its own shared Bulletin-board. Posts to this layer provide supporting materials for the underlying activity that other participants in the activity may view (Or, if they'd like, keep for themselves). This actually means a great deal, since any object at all can be shared this way, including many objects that the activity itself may not provide support for. For instance, though one couldn't paste a song inside a drawing (no compound document), a song posted to the Bulletin Board layer could provide inspiration for it. Similarly, it provides a means of collecting materials relevant to the task at hand within the activity. Rather than having 5 individuals each pasting images of a shark directly into the drawing, they could instead post them to the Bulletin Board for others to see and discuss before deciding which to use as a basis for the drawing. Thus, Bulletin Boards provide a space for gathering research and supporting materials, and holding discussions around both them and the activity.

View Source

While Bulletin-boards provide a layer of abstraction on top of any given activity, the View Source button allows one to look behind the activity, peeling away layers of abstraction in order to reveal the underlying codebase which makes it tick. This feature will integrate cleanly with the olpc:Develop activity, encouraging children to view, modify, and redistribute variations on the activities they use. Through collaboration and sharing, a garden of home grown activities will begin to develop on the laptops, created by the children themselves.

The Journal

- See Journal and Design Team/Proposals/Journal for new design images.

The Notion of "Keeping"

We believe that the traditional "open" and "save" model commonly used for files today will fade away, and with it the familiar floppy disk icon. The laptops do not have floppy drives, and the children who use them will probably never see one of these obsolete devices. Instead, a more general notion of what it means to "keep" things will prevail. Generally speaking, we keep things which offer value, allowing the rest to disappear over time. The Journal's primary function as a time-based view of a child's activities reinforces this concept.

Most of us have heard the "save early, save often" mantra, largely ignored it, and incurred the consequences. Sugar aims to eliminate this concern by making automatic backups. This lets the children focus on the activity itself.

The physical analog for an Activity is paper, pencil, & writer at a desk, canvas, paint, & artist at an easel, clay & hands at a wheel, or sidewalk, chalk, & children at a driveway. They exist as created and modified. No 'saving' action, per se, is needed. The 'Keep' toolbar button (proposed to be 'Copy', [1]) provides the capability to replicate the current state of the Activity into a new, separately available* Activity object in the Journal. Outside of software culture, such rapid and perfect replication has few physical analogs, and perhaps so has been a point of confusion.

- * Note: The Keep(Copy) action currently produces an object that shares an ID with its parent and so may not be opened simultaneously with its parent in the same Sugar instance. (This is a bug.)

Incremental backups occur regularly and are also triggered by such activity events as changes in scope, new participants, etc. To cater to the many needs of the editing environment, activities can also specify "keep-hints" which prompt the system to keep a copy. For instance, a drawing activity may trigger a keep-hint before executing an "erase" operation immediately preceded by a "select all". Of course, a child may choose to invoke a keep-hint by selecting the "keep in journal" button, but the increasing adoption of this new concept of keeping should ultimately eliminate this.

Based on the Object model associated with files, each kept Object is, technically speaking, a separate instance of the activity that created it. This eliminates the need "to open" a file from within an application, and replaces the act of opening with the act of resuming a previous activity instance. Of course, a child will have the option to resume a drawing with a different set of brushes, or resume an essay with a different pen, and will so be provided with an "open with" (a different tool kit)-style of functionality; but, no substitute for an "open" command will exist within an activity's interface.

Deprecating Hierarchy

Temporal Organization

Along with the idea of implicit keeping, the laptops will drastically minimize the hierarchical filesystem as a means for organization, replacing it with a temporally organized list of activities and events, furthering the Journal metaphor. This drastically simplifies the auto-keeping behavior, since it eliminates the need to specify a location in which a newly started activity should be kept; naturally, the newly started activity will appear as the most recent entry in the journal.

Temporal organization functions naturally in the absence of explicit or hierarchical methods, since humankind's intrinsic relationship to time gives them, at the very least, a relative notion of "how long ago" something happened. By moving back through the Journal, a child can simply locate the period in time within which she knows she made something, and then employ additional use of searching, filtering, and sorting to pinpoint exactly what she's looking for.

Falloff

Due to the laptops' limitations in storage capacity, the potential exists for the Journal to contain so many entries that no more may be written. However, the frequency of such occurrences is limited by temporal falloff, which tidies up the Journal contents and keeps space available for new entries. One might think of this as an intelligent combination of garbage collection and disk defragmentation.

The driving principle here is that of temporal granularity, derived directly from our very capacity for human memory. Our minds, generally speaking, maintain a high level of granularity with respect to very recent events, but only a low granularity for events from several years ago. Moreover, this granularity tends to follow a logarithmic curve, where the past few minutes remain quite clear, the past few hours more blurry, and by last month quite vague. When we look years into the past, only specifically memorable events stand out in our minds.

On the laptops the policies are a bit more strict, but the principle remains the same. With a finite amount of memory, there must exist some means of managing what's remembered, or kept; and what's forgotten, or erased. An intelligent algorithm will assist children in identifying "forgotten" entries. Taking into account how old an entry is, how many times she's viewed it, how recently she's worked on it, how many hours she's worked on it, how many people she's worked on it with, its tags, and even more forms of automatically generated metadata, the Journal can suggest to her those entries which it feels can be erased. She will then have the opportunity to review those items prior to their erasure, if she wishes, and can keep any she still feels attached to.

In a time where gigabytes have become cheap, many of us still manage to fill our hard drives. Excepting the cases of multimedia collections of audio or video files, much of that space is consumed by files we either don't remember we ever made, or will never open again. On the laptops, where space is precious, so too will be the objects and entries that remain in the journal years down the road. The temporary, the experimental, the duplicate, and the unwanted files will naturally fall off the bottom, maintaining a browsable history of those that remain important to the children.

Journal Entries

Implicit

Implicit journal entries will be the most common. These appear as the result of many kinds of a child's interactions with her machine, but most commonly when engaging in an activity. Other implicit entries might appear when she takes a photo, or receives a note from a friend, or downloads a file from the Web. In all of these cases, the journal entry itself has a basic format which conveys important information about the event which created it. Most importantly, the associated Object - the photo, the message, the drawing, the story - becomes embedded within the entry. It also includes key metadata, such as its name, when it was made, and who collaborated on it.

The journal entry also provides some means to interact with it. For instance, each entry has a description field where a child can tag it with meaningful related words which will make searching for it in the future a breeze. This field will automatically receive any tags that the activity itself associates with the entry. In addition to this tag field, several buttons will allow direct manipulation of the Object, making it possible to resume the activity, place the Object on the clipboard, send it to a friend, print it, or erase it, among others.

Note

In addition to implicit ones, children have the opportunity to create several special kinds of entries on their own. The first of these, the Note, has the simplest form. Taking a cue from a traditional journal, a Note entry simply provides a large text entry field. This freeform entry allows the children to write down short descriptions of their day to day experiences, just as one would within a real journal. Providing this layer of personalized entries further emphasizes the idea that the Journal really does provide more than a filesystem, as an actual record of events and interactions of the children with the laptop and with their peers.

In practice, children may also use this feature as a means of jotting down a note to themselves - a reminder. In these instances, a simple control within the entry will turn the note into a "to-do" note. As a to-do entry, it will have a checkbox indicating its completion status. By filtering the Journal to show only these entries, it doubles as a basic to-do list, providing another useful tool for learning organizational skills.

Clipping

Clippings serve a slightly different purpose in the journal. Similar in spirit to notes, a child can create a clipping from anywhere, or from within any activity on their laptop. As an extension of the copy to clipboard idea, clippings copy a selection - some text from a chat session with a friend, an image from a web page, etc. - directly to the journal for safekeeping. This provides a quick and easy way to keep a quick record of anything that you might want to keep around for future reference: a phone number, a link, a password, etc.

Event

Taking the temporal aspect of the Journal one step further, Events act like "future" journal entries. By specifying a name for the event, a brief description, and a time, these Journal entries serve as a basic planning system. A control within the entry also enables an audible alert, so that Events can act as alarms. Events also tie in closely with some implicit actions of the laptops. For instance, a child might want to go on a photo safari with her friend after school. While still in class, she sends him an invitation to join a photo capture activity, but schedules a time of 3:00. He then receives an invitation, as usual, but upon accepting it receives an Event entry in the journal, with a reference to the scheduled activity, instead of immediately entering it. When 3:00 arrives, both children receive notifications that their scheduled event is about to start, and join each other both physically outside and virtually in the referenced capture activity.

Progress Indicator

In many cases, entries will appear at one point in time but the desired result of the entry won't be immediate. This might occur, for instance, when downloading a file from the Web, receiving a file from a friend, restoring a file from the server, or saving a large Object such as video or audio data. All of these processes take some non-trivial length of time, and so when necessary, Journal entries will provide a progress indicator stage. When the download, transfer, or task begins an entry will be created in the journal to indicate that. This entry will include a progress bar with estimated time until completion; once completed, it will transition to a standard entry. This makes the Journal a consistent place to keep track of progress, and also provides an easy means to pause and resume transfers, which will prove extremely useful when in areas with intermittent connectivity.

The Power of Metadata

Despite the flatness of the Journal, finding past entries shouldn't prove difficult thanks to a tagging structure built from the ground up for the laptops. By associating relevant descriptive words with each journal entry, searching for an entry becomes as easy as describing it. These descriptions will manifest in two ways, tagging and metadata. The former provide a straightforward manner for the children to describe and organize their stuff, while the latter provides a more technical means by which activities can associate relevant data and tags with all Journal entries they create.

Tagging

Tagging will become a fundamental process for all types of data and activities on the laptops. Fortunately, children have a natural inclination to describe their world and the things they see and do. This actually aids kids in learning, as they will enjoy describing the drawing they've made, the stories they've written, or the composition they produced, and can learn new vocabulary in doing so. Of course, the kid-like desire to describe things doesn't detract from the usefulness of this tag-based system as they grow older.

As such an integral part of the system, the tagging interface will be exposed in various places. Of course, as mentioned, each journal entry will have a field for tags. Likewise, each open activity instance will have a tag field adjacent to its name field, so that the act of naming a particular activity or Object becomes associated with describing it in their minds. Additionally, activities could offer specific places within the interface for tagging to occur, such as in the description field for a photo the child just took.

Metadata

Metadata adds an additional level of sophistication to the tagging model. Rather than thinking of this as data about data, consider it a means of tagging tags. Metadata on the laptops will be an extension of the basic tagging model where the tag itself consists of a key:value pair. Or, you could simply consider a tag to be a metadata pair with a null key. Whichever way you look at it, this categorization of tags has powerful implications when it comes to organizing and categorizing data.

The Journal itself assigns a variety of useful metadata tags to entries as they appear. These include the time of the entry, its sharing scope, who participated in the activity, its size, and more. The Journal will also keep track of other useful metadata, such as the number of times a child views a particular entry, the number of revisions an entry has gone through, etc. Likewise, activities will deal primarily with metadata rather than simple tags. This allows activities to define specific parameters, or keys, that make sense for the Objects they produce, and then assign values to those dynamically. In a music composition activity, for instance, potential keys might be beats per minute, the key the composition is written in, the length of the track, and the composer, among others. See the sorting section to fully understand the usefulness of this metadata within the Journal.

Of course, since tags and metadata both follow a very basic format, children can assign their own metadata associations with Journal entries once they have enough experience simply by typing key:value pairs into the description field.

Powerful Search, Filter & Sort

Searching

The search field provides the most direct means of locating a particular Journal entry, returning instant results as the search is typed, and offering auto-completion for popular tags. In order to find anything on their laptop, a child need merely describe it, since the tags she's associated with it already appear within its description field. Her searches also apply to the metadata associated with the entry by either the Journal or the activity that created it, making it even easier to find things.

For simplicity, the search field will employ OR logic to all terms entered, which ensures the least amount of confusion when used by children who don't yet understand boolean logic. As such, a search for "orange cat" will return a list of everything orange and also every cat. Of course, any entries tagged with both orange and with cat will match more strongly, and will automatically filter to the top of the results. However, in keeping with a primary goal of the laptops, this won't eliminate the possibility for more complex boolean searches. Full support for AND, OR, NOT, and parenthetical grouping of terms will be built into the search engine, providing advanced functionality for those who desire to enter more complex queries.

Since the laptops will find themselves in the hands of many children, additional modifications to the search algorithm will assist them as they grow. The youngest children who receive them will still be learning how to spell, and those that can may still require some time to learn typing skills. For these reasons, a fuzzy match algorithm will assist the children, returning some results even when the corresponding tags don't match what they typed exactly. This algorithm is adaptive, and so as they become more comfortable with their language and with using the technology, the extent of the fuzziness and therefore the number of fuzzy results returned will lessen, preventing false matches from aggravating more advanced users. Several other kinds of fuzziness could also be applied, though such possibilities are only speculation at this point. For instance, fuzzy matches based on thesaurus entries could turn up items tagged with "funny" even when the child searches for "humorous". Likewise, translation fuzziness could return an entry tagged with "cat", even though the child searched for "gato." These advanced fuzziness algorithms could prove invaluable in a laptop community that has been built with sharing and collaboration in mind.

Filtering

Support for basic filtering also exists within the journal. The search and filter functionality appear together in the toolbar, since searching could also be interpreted as filtering by tags. Additionally, their appearance together allows an easy method for the children to visually construct their query in a sentence-like format, with relevant parts of their query displayed as icons — just as those within the entries themselves — for visual reinforcement.

Several fundamental filters exist. First and foremost, there is an advanced date filter, which can only be expected in a Journal organized temporally by default. This control will present a timeline to the child, with visual indication over the length of the timeline of the number of entries present in the Journal from any given point in time. By expanding and contracting the selected area she can select anything from a single day to all time, and by sliding the selection through time, she can filter out all entries that don't lie within the specified range. Other basic filters include the activity that the entry represent, and the activity participants.

Other available filters allow children to locate specific kinds of entries. For instance, a child may want to view all entries that have been tagged by the Journal for possible removal when memory becomes low. They may also want to see all their notes, or to-dos, or events. They could also show only starred items, or in progress items, and more. The system will provide adequate flexibility for finding anything in the Journal nearly instantaneously.

Sorting

Whereas searching and filtering provide a means of defining what entries get shown in the list of results, sorting determines how those entries are organized. A unique approach to sorting on the laptops makes the metadata associated with entries even more valuable. The sort bar, which the child can expand in order to more precisely control their view of the journal, offers a popup menu from which a number of options such as date, title, activity, size, participants, and others may be chosen. In addition to this fixed list, a dynamic list of options also appears, providing a list of metadata keys that are present in the majority of the entries within the results list, the utility of which will become apparent below.

The true functionality of the system arises from "then by" sorting. When desired, a child can specify up to three levels of sorting hierarchy. This feature shouldn't be overlooked, since it serves as an extraordinarily powerful means of viewing and organizing data hierarchically, even when no hard hierarchy exists. In fact, when used to its full advantage this approach can be more useful than a hard hierarchy, since the order of the hierarchy can be adjusted dynamically to suit the child's needs at the time. And, in conjunction with the intelligently compiled list of metadata keys on which to sort, children can not only find what they're looking for, but can browse through their journal in any way that suits them. Consider, for instance, that a child filters her journal so that all of her music appears in the results. Since nearly every song Object in her Journal has metadata keys for artist, album, track, and year, she could sort by these keys to arrange her music collection for browsing. Sorting by artist, then album, then track she can obtain a traditional view of her music. In order to view a discography for each artist, on the other hand, she could sort by artist, then by album, then by track. Or, to see a timeline of her music, she could sort by year, then by artist.

This powerful sorting method isn't necessarily limited solely to a bunch of songs, or pictures, or other specific type of data. Since many forms of metadata will apply across Object types, the possibilities are nearly limitless.

Implicit Versioning System

As mentioned before, the laptops automatically save, or "keep", objects in the Journal at regular intervals. This eliminates the need for the children to constantly worry about saving, and reduces the chances that an unexpected circumstance will cause data loss. These individual keep events are incremental, meaning that the changes within the file are kept in a nondestructive manner. Therefore, the Journal not only stores Objects as children create them, but also keeps track of the revision history for each one. This allows the Journal to function as a versioned filesystem.

The space limitations on the laptop cause some concern with the mention of revision history. However, the differences between revisions will often be small. Additionally, Objects with large revision histories provide one easy way for the journal to regain valuable space when memory becomes tight, since it can collapse the history, storing only every few automatic revisions in addition to those explicitly kept by the child.

Automatic Backup and Restore

Backup

In most locations where laptops deploy, a nearby school equipped with a server will provide additional functionality when children bring their laptops within range. This server has one major implication for the Journal: backup. Due to limited storage space on the laptops, children will have to choose to erase older entries to make way for new ones. The automated backup system will ensure that, even once their creations leave their own laptops, they will remain available on the school server. This process will happen in the background, fully automatically, anytime the child comes within range and bandwidth allows. Her Journal will keep track of which entries have and have not yet been backed up, taking this into account when recommending items for removal.

Restore

The backup service provided by the server will allow several types of restoration, based upon the child's needs.

Full restore functionality provides a fail-safe for the children. Though the ruggedness of the laptops should minimize the need for a full restore, any event which causes permanent loss of any or all data on a laptop can be recovered from nearly completely from the backup files. These files also provide a means of restoring the child's settings and data should they for any reason ever need a new laptop. In practice, this is a temporal restoration, recovering all files stored on the backup server within a given time period from the present.

The backup server will also provide partial restores, which allows children to select individual objects and entries to recover. Any recovered items will appear as a new Journal entry on the date of recovery. This form of restoration will occur with much greater frequency, purposed mainly to restore an accidentally deleted entry from a week or so ago, while flexible enough to restore any entry ever backed up on the server.

In addition to these hard restoration methods which physically copy the data back onto the children's laptops, the server will also provide soft restore functionality, allowing children to browse through the backups on the server directly from within their Journals. Since this browsing functionality will integrate cleanly with the entries stored on their own laptops, the children will be able to search, filter, sort, and view anything they ever entered without having to think about the technicalities of the data's physical location. Apart from a visual indication within the entry, the experience of browsing through backups will be seamless. Using the temporary restore method, children can browse through their past creations, much as we might browse through a photo album. They will have full ability to resume any instance of an activity, to view its contents. A copy-on-write approach will be taken, so that if a child attempts to modify a temporarily restored item, it will behave identically to a partial restore for that Object, writing the modified revision into a new journal entry.